Aesthetic Experience and Meaning, From the Developmental to the Transcendental

The process of artistic creation, especially in the West, has generally been a self-conscious one, constantly probing into the nature of art with endless questioning. Among these questions are most fundamentally: What is art? Must art be beautiful? And if so, can we form objective standards of beauty? While philosophers have been considering the nature and significance of art for centuries, only recently have we been able to consider the aesthetic experience as a biological and neurological phenomenon, with deep roots in our evolutionary history— one which is not merely a reflection of evolutionary imperatives, but more importantly a tool for extracting meaning from the mundane and shaping man’s understanding of himself and the world.

In their paper

The Science of Art: A Neurological Theory of Aesthetic Experience, researchers V.S. Ramachandran and William Hirstein propose a number of compelling laws of aesthetic experience that elucidate why humans respond to art in the way that they do. These laws have also been critiqued by Cynthia Freeland in her book

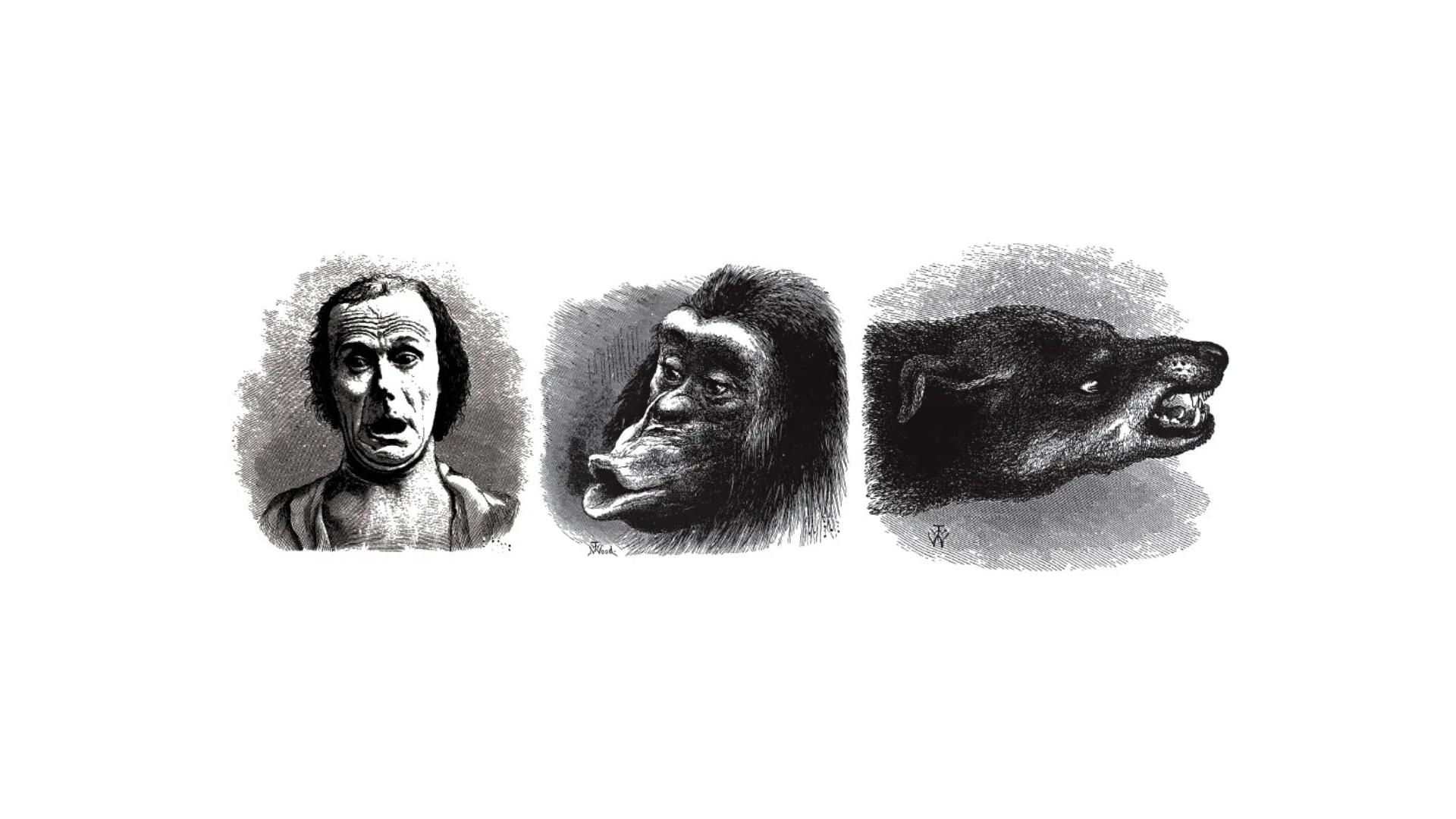

But Is It Art? An Introduction to Art Theory. One of their proposed laws, the peak shift principle, is praised by Freeland for its explanatory value with regard to caricature and other extremes in the arts. (Freeland, p. 173 para. 1) If a little bit of something is adaptive (such as strategically advantageous natural landscapes, exaggerated secondary sexual characteristics, etc.), it makes sense that this could easily be taken to extremes, and become manifest in aesthetic preference. This could perhaps explain exaggerated female forms in some artwork. Freeland, however, takes issue with the overall focus on the ‘evolutionary imperatives’ invoked by the authors as the basis for much of aesthetic experience, especially those having the human body as the focus. Freeland writes, “his choice of the verb ‘titillate’ in the quotation above seems all too apt, because many of the article’s illustrations are depictions of erotic nude females. The article suggests that ‘our’ interest in their beauty derives from universal evolutionary imperatives—a point that cries out for some Guerrilla Girls intervention!” (Freeland, p. 172 para. 2) Despite feminist protestations, the experience of beauty certainly does derive from such biological imperatives, be they of a sexual nature or not (such as the fruit-finding adaptivity of colour vision (Osorio, p. 598)). It may be that both sexes derive an interest from the biological imperatives, but in different manners; while the basis for male interest in the female form is obvious enough, women too derive important information about the nature of female desirability through such art. Additionally, “there is evidence that women may direct as much visual attention to, and be as physically aroused by, the sight of (nude) women's bodies as men's.” (Bogaert, p. 19 para. 1) The interest that a woman takes in beauty can serve to affirm her own desirability, reflected back through art and displayed as an object of admiration; this is evolutionarily adaptive insofar as this appraisal allows the woman to correctly assess her mate value compared to women considered as standards of beauty, and “demand an optimally high price for her sexual resource.” (Bogaert, p. 12 para. 2) When viewing other women in sexually suggestive contexts, women (especially more so than men) typically experience “‘positive projective identification’ […] able to "project” themselves onto the female protagonist.” (Bogaert, p. 16 para. 1) Thus, women may also take an evolutionarily adaptive sexual interest in female nudes, which is transferred into a desexualized aesthetic interest as it is for men. Though Freeland does not address it, another of the most compelling aesthetic laws offered by the authors is that of symmetry. As the maintenance of bilateral symmetry in animals is extremely bioenergetically taxing, the ability to maintain a symmetrical phenotype in the presence of environmental instability, disease, and as the authors note, parasites (R&H, p. 34 para. 1) is a sign of good genes, and should be inherently attractive to humans.

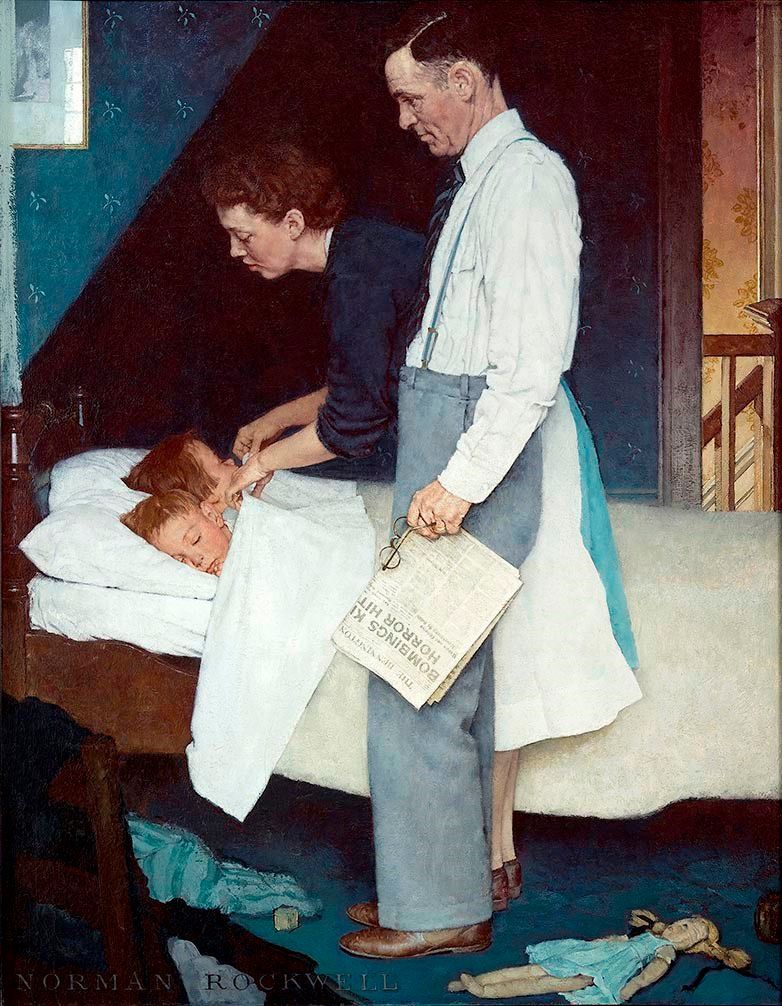

Beyond the biological issues, Freeland criticizes Ramachandran and Hirstein’s claim that “all art aims at beauty,” because “we know from Chapter 1 (on blood) that this is not true.” (Freeland, p. 172 para. 2) Despite being confidently stated, it was not shown to be true that not all art aims at beauty, and a compelling argument can be made that all real art aims at beauty, in at least some capacity. It can be simultaneously true that beauty is not the aim of an artwork, while also being a requisite that such a beauty is present; an artwork can also be beautiful without being visually beautiful, through the themes that are being addressed. Take Freeland’s argument of blood in art, for example; in the European tradition, depictions of rituals or myths involving blood aim at the beauty of the story being depicted, not the blood; the blood is significant only so far as it symbolizes the bravery, or the sacrifice. What we find beauty in is those ideals being expressed, not the blood— hence why the bleeding wounds of Christ on the cross can be profoundly beautiful, expressing the ultimate sacrifice, and the rags soaked in HIV-infected blood (Freeland, p. 4 para. 1) are not. Despite all these criticisms, Freeland ends on a seemingly contradictory note of ambivalence in stating that “art inevitably depends on perceptual and cognitive processes.” (Freeland, p. 173 para. 1) Why this should not also include those based upon biological and reproductive imperatives is unclear.

Throughout the book, though centralized in chapter 6, Freeland lays out the core tenets of her views on art and its interpretation. Her central belief is that though art is a “cognitive enterprise,” there is not “one true account of ‘the’ cognitive contribution made by an artwork.” (Freeland, p. 175 para. 1) Freeland’s view on art interpretation and critical analyses is that they “help explain art—not so as to tell us in the audience what to think, but to enable us to see and respond to the work better for ourselves.” Without defining the parameters of such interpretations as Hume did, Freeland gives a Humean view on (qualified) art critics, whose joint verdict he deemed the “true standard of taste and beauty.” (Hume, p. 229) Both believe that such people can help guide the public thought on works of art.

Although carefully considered and measured, Freeland’s views tend to err on the side of vaguery and fence-sitting. Part of her definition, for example, that artists “express thoughts and ideas in a way that can be communicated to audiences, enriching our experiences” and “do this in a context, and their ‘thoughts’ serve some specific needs within that context” (Freeland, p. 175 para. 1) is painfully imprecise and inclusive. I can express thoughts and ideas, in a context, that serve specific needs within that context, and enrich others’ experiences, with something like an instruction manual— but we would hardly consider this art. Her views are also perhaps too permissive when it comes to what constitutes art. In stating the importance of cultural context to an artwork, Freeland points out that Warhol’s

Brillo Box

would not make sense to people in ancient Athens (Freeland, p. 149 para. 1), and thus we “must know ‘external’ facts before trying to acquire the ‘internal’ attitude of appreciation” of the work (Freeland, p. 64 para. 1); in contrast, much of the art produced in ancient Athens still holds immense meaning to modern humans, even without the relevant surrounding information or explanation. If we are to conclude that Warhol’s boxes are in fact art, it seems safe to say that some works of art are then simply worse than others.

All things considered, I argue that the laws of Ramachandran and Hirstein (most notably the ensuing two) point toward both the psychobiological and metaphysical significance of art— namely, the extraction of meaning from the mundane. This is a process available both to the artist and to those who experience the art. One of the eight laws proposed by Ramachandran and Hirstein primarily relevant to meaning-making is that of ‘art as metaphor.’ The utility of a metaphor is that it “allows us to ignore irrelevant, potentially distracting aspects of an idea or percept […] and enables us to ‘highlight’ the crucial aspects.” (R&H, p. 31 para. 1) It is the act of detecting the signal amongst the noise, in a world that is composed mostly of the latter. A truly good metaphor, visual or otherwise, is able to “evoke an emotional response long before the metaphor is made explicit […] even before one is conscious of it” (R&H, p. 31 para. 1) The painter Jannik Hösel speaks of something similar, stating in an interview, “Pure symbolism can really go astray […] A bad vanitas painting, for example: the skull represents death, this flower represents sorrow, the worm represents decay […] very low-resolution meanings for one thing. A good symbol is when there is more in it the deeper you go, so it unfolds itself. That’s what Odd [Nerdrum] also recently said: ‘A good painting is when there’s more in the painting than the painter knows— if there’s something more than he was conscious of while he was painting it.’” (Hösel, 52:10) The artist and the viewer seek then not merely conveyance or experience of an emotion, but fundamentally to find something out about himself and the world. In this way, a (visual) metaphor can act as a sort of tool for bringing into consciousness that which has been obscure. It is likely that the more adept the artist and the interpreter, the more they are able to see the connection between “superficially dissimilar events” (R&H, p. 31 para. 2) to extract out what is not only common, but meaningfully common between them— and perhaps the level of skill lies in the level of dissimilarity between the multiple ideas which they are able to synthesize into a gestalt. This synthetization is the process by which we are able to “transcend tokens to create types” (R&H, p. 31 para. 2), harkening back to the Platonic ideals and the essences of things which exist separately and above the mere instances.

Another of the eight laws salient to how the artist and viewer extracts meaning from an artwork is that of the ‘peak shift’ effect; in art, this effect relies upon “the ability of the artist to abstract the ‘essential features’ of an image and discard redundant information.” (R&H, p. 17 para. 3) This is also essentially what an artist is doing when he invokes a metaphor. Though peak shift can occur as a natural process, the artist can also cause this shift through an exaggerated deviation from the norm— as the authors note, often “in a manner that is not obvious to the conscious mind.” (R&H, p. 20 para. 1) The works of Van Gogh and Monet, for example, may (respectively) “excite the visual neurons that represent colour memories of those flowers even more effectively than a real sunflower or water lily might.” (R&H, p. 20 para. 1) In this idea, we again return almost to the Platonic idea of the artist who is able to tap directly into the world of forms, to create an artwork that is ‘realer than real,’ which unveils something to the world formerly shrouded in the profane, normally inaccessible. The authors speak of “a mnemonic component of aesthetic perception, including, the autobiographical memory of the artist, and of her viewer, as well as the viewer’s more general ‘cognitive stock’ brought to his encounter with the work.” (R&H, p. 20 para. 2) While it seems that Ramachandran and Hirstein are postulating the presence of imagery pulled from the artistic canon and the culture at large, I suggest that a large amount of this imagery is also a priori and archetypal. This is perhaps what Jung was aiming at in the mapping of his archetypal figures, “the numinous, structural elements of the psyche [that] possess a certain autonomy and specific energy which enables them to attract, out of the conscious mind, those contents which are best suited to themselves.” (Jung, p. 213 para. 344) The archetypes therefore allow for a flexible plethora of possible manifestations through imagery, left up to the artist and viewer to manifest and interpret.

This meaning-making (or perhaps finding) out of the chaos of the world is the final cause of art, the reason for its existence and for man being inexorably drawn to it. All theories of art that fail to take into account the necessary meaningfulness of an artwork cannot fully encapsulate its essence. Even Anderson’s definition, which includes “culturally significant meaning,” (Freeland, p.77 para. 2) fails to take into account that the work must not just contain a meaning, but must be interpreted as meaningful in the larger mosaic of the life of the individual; it must allow us to make sense of our experiences, in relation to ourselves and others. As Roger Scruton wrote in Beauty, “This ‘blessed rage for order’ is present in the very first impulse of artistic creation: and the impetus to impose order and meaning on human life, through the experience of something delightful […] In the highest form of beauty life becomes its own justification, redeemed from contingency by the logic which connects the end of things with their beginning.” (Scruton, p. 128 para. 1) We are drawn to art, especially its beauty, because it provides an ideal to which we may compare ourselves and serves as an orienting guide for ordering our values and goals, and ultimately, being more than what we are. This aligns perhaps most closely with Dewey’s theory, insofar as he “emphasized art’s role in enabling people to perceive, manipulate, or otherwise grapple with reality […] to enrich their world and their perceptions.” (Freeland, p.166 para. 2) I depart from Dewey in arguing that the individual, not the culture or community, is the central agent and important factor in the artistic experience. It facilitates Jung’s concept of individuation, which through the experience of the individual “brings to birth a consciousness of human community precisely because it makes us aware of the unconscious, which unites and is common to all mankind." (Jung, p. 158 para. 227) Therefore in the final analysis the specific culture is not crucially relevant.

In summary, the human experience of beauty undoubtedly originates in the evolutionary history of our ancestors, with traits that conferred an advantage in survival of the animal or its offspring persisting in the population and eventually coming to compose our aesthetic sensibilities. Though the experience of art and beauty may originate in the purely mechanistic workings of evolutionary biology, it does not mean that this is where it must end, nor does it take anything away from the aesthetic experience. For example, although feelings of romantic love are evolutionarily adaptive insofar as they facilitate pair bonding and effective rearing of offspring, scarcely anyone interprets the ultimate meaning of love in the human experience to be one of pure adaptivity. Beyond the mere neurological function, art can serve as a profound source of meaning in the life of man, allowing him to bring order from chaos, and interpret and understand the world and his life in it.

References

Bogaert, A. F., & Brotto, L. A. (2014, June 14).

Object of Desire Self-Consciousness Theory. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. https://sci-hub.se/10.1080/0092623x.2012.756841

Freeland, C. (2002). Blood and beauty.

But Is It Art? An Introduction to Art Theory

(p. 4). Oxford University Press.

Freeland, C. (2002). Cognition, creation, comprehension.

But Is It Art? An Introduction to Art Theory (pp. 149, 166, 172-173, 175). Oxford University Press.

Freeland, C. (2002). Cultural crossings.

But Is It Art? An Introduction to Art Theory (pp. 64, 77). Oxford University Press.

Hume, D., & Millar, A. (1757). Of the Standard of Taste. In

Four dissertations: I. The Natural History of Religion. II. Of the Passions. III. Of Tragedy. IV. Of the Standard of Taste

(p. 229). Essay, Printed for A. Millar, in the Strand.

Jung, C. G. (2014).

Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 16: Practice of Psychotherapy (Vol. 16) (p. 158). Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (2014).

Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 5: Symbols of Transformation (Vol. 5) (p. 213). Princeton University Press.

Osorio, D., & Vorobyev, M. (1996, May 22).

Colour Vision as an Adaptation to Frugivory in Primates.

Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. https://sci-hub.se/10.1098/rspb.1996.0089

Ramachandran, V. S., & Hirstein, W. (1999). The Science of Art: A Neurological Theory of Aesthetic Experience.

Journal of Consciousness Studies, 15–51.

Scruton, R. (2009).

Beauty

(p. 128). Oxford University Press.

Tuv, J. O., & Hösel , J. (2023, February 15).

Jannik Hösel on How He Taught Himself to Paint and His Take on the Role of Symbols in Storytelling. Cave of Apelles. https://youtu.be/6atoJEs39fs?t=3131 (52:10 - 53:09).

Cover image: The Creation of Adam (Detail), 1512, Michelangelo.