Dress, Architecture, & the Public Landscape

Every design problem begins with an effort to achieve fitness between two entities: the form in question and its context. The form is the solution to the problem; the context defines the problem. In other words, when we speak of design, the real object of discussion is not the form alone, but the ensemble comprising the form and its context […] The rightness of the form depends, in each one of these cases, on the degree to which it fits the rest of the ensemble.

—

Christopher Alexander,

Notes on the Synthesis of Form

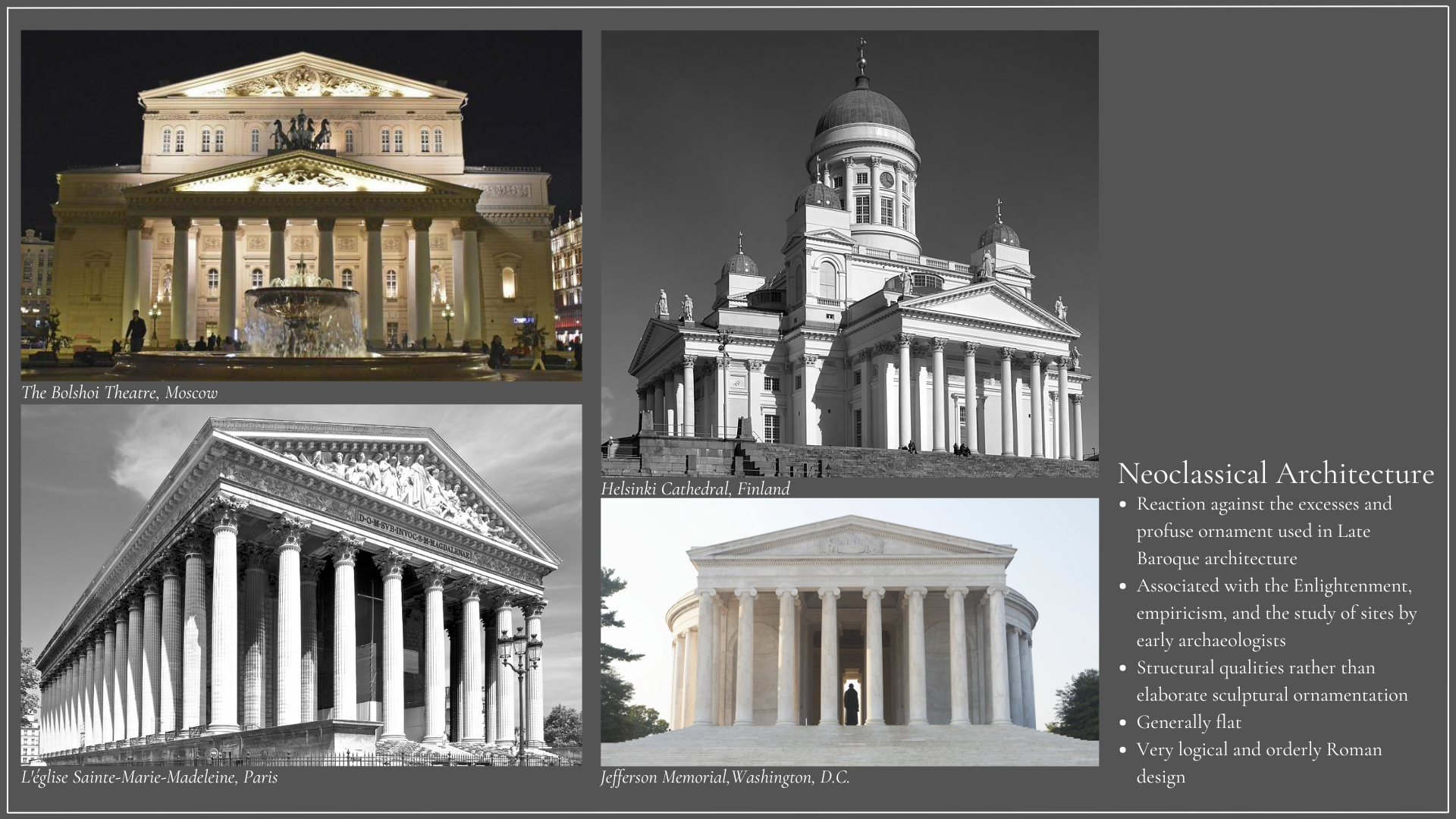

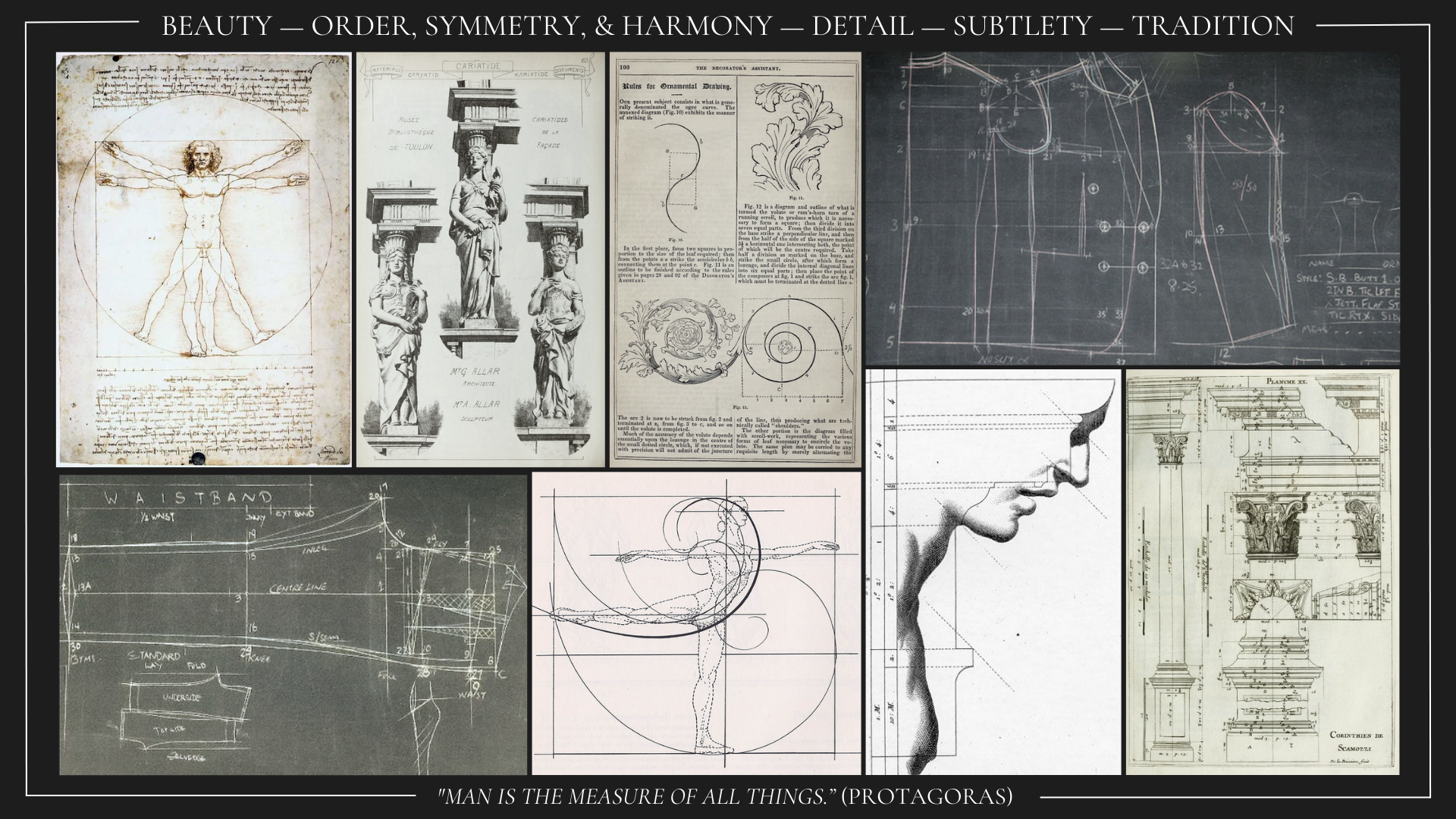

Architecture and dress, like other cultural arts, have suffered from the same afflictions of modernity: the dominance of functionalism at the expense of beauty, the crisis of sustainability driven by disposability, and the devaluation of craftsmanship. Architecture has been reduced to monotonous glass and concrete structures, while dress has become a landscape of mass-produced, synthetic garments designed for obsolescence rather than enduring quality. This decline is not merely random, but rather reflects a broader cultural shift— one that dismisses beauty as frivolous rather than recognising it as essential to human flourishing.

Christopher Alexander, in Notes on the Synthesis of Form, writes that “every design problem begins with an effort to achieve fitness between two entities: the form in question and its context… The rightness of the form depends, in each one of these cases, on the degree to which it fits the rest of the ensemble." In this way, cities and towns are shaped not only by the built environment, but also by the people who inhabit them. Just as architecture influences the character of a place, so too does dress contribute to the visual and cultural identity of its surroundings; the way we construct our built environment and the way we present ourselves are intertwined, shaping not only how we see the world but how we experience our place within it. The erosion of either leads to a broader dissolution of aesthetic and civic coherence— and when beauty disappears from the built environment, it has also disappeared from the culture that inhabits it. Yet modern discourse often relegates beauty to the subjective and optional, dismissing its role in shaping both individual lives and public spaces. The decline of architectural and sartorial traditions reflects an impoverishment of the human experience, leaving individuals and communities alienated from their surroundings.

At the root of this crisis is not only a philosophical rejection of beauty but a misunderstanding of the meaning of ‘sustainability.’ Modern sustainability efforts in both architecture and dress often focus on material choices and production processes while overlooking the deeper issue: the failure to create objects worth preserving. As Scruton aptly states in

The Aesthetics of Architecture, “Beautiful buildings change their uses; merely functional buildings get torn down.” The same is true for dress— garments are discarded not because they are worn out, but because they were never deeply valued to begin with. True sustainability lies not in endless innovation but in the creation of enduring beauty. When we build and design with longevity in mind, we cultivate not just material preservation but a deeper cultural continuity across time. Such a continuity was once maintained in part through the aesthetic heritage of different regions; both architecture and dress reflected the unique history and character of their surroundings, reinforcing a sense of belonging. Vernacular buildings and folk dress embodied cultural identity, anchoring individuals within a shared artistic and historical lineage. Today, globalist architecture has rendered cities indistinguishable from one another, while our clothing has been reduced to a monotonous global wardrobe of jeans, sneakers, and t-shirts. The consequences of this homogenisation are profound. A city that looks like every other city ceases to be a city in the true sense; it becomes a collection of structures without a soul. Likewise, when dress loses its connection to artistry and locality, it loses its ability to speak to something higher than mere utility.

Fundamentally, at the heart of both good architecture and dress is techne— the knowledge of how to create through skilled practice. The devaluation of craftsmanship has led to a loss of mastery in both fields. Mass production prioritises speed over artistry, while digital technologies, though powerful, often generate algorithmically dull designs rather than enhance human creativity. To reclaim beauty in design, we must also reclaim techne. A tailor, like an architect, must possess both theoretical knowledge and the skill to bring it to life. A classical architect understands why an entablature must possess certain proportions; a tailor understands why a lapel must be cut a certain way to maintain balance and elegance. These principles, once second nature to designers, must be reintegrated into contemporary practice if we are to restore the aesthetic richness of both our cities and our clothing.

As Roger Scruton puts it so well in

Beauty, “this attempt to match our surroundings to ourselves and ourselves to our surroundings is arguably a human universal. And it suggests that the judgement of beauty is not just an optional addition to the repertoire of human judgements, but the unavoidable consequence of taking life seriously, and becoming truly conscious of our affairs.”

This attempt to match our surroundings to ourselves and ourselves to our surroundings is arguably a human universal. And it suggests that the judgement of beauty is not just an optional addition to the repertoire of human judgements, but the unavoidable consequence of taking life seriously, and becoming truly conscious of our affairs.

—

Roger Scruton,

Beauty